ExaLotto Whitepaper

Abstract

We hereby provide the design specification of ExaLotto, a lottery game based on the Ethereum Virtual Machine (“EVM” in the following).

The game will be managed as a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (“DAO” in the following).

Motivations

Lottery games have ancient origins tracing back to the Chinese Han Dynasty, between years 205 and 187 BC. The core idea of the game is that every player pays a small amount of money and a randomly chosen lucky winner gets the money from all contributions.

Unfortunately, classic operation of such games requires a central running authority and subjects them to several issues:

- Censorship: some countries make some or all lotteries illegal.

- Locality: lotteries are usually State-managed and subject to local regulations, making them impossible to extend across borders and turn global.

- Obscure or unfair prize allocation: in a typical lottery game a share of the jackpot is attributed to every winning category, but the way these shares are allocated is almost never explained and is often unfair.

- Outright scams: classic operation provides little to no guarantees about the fairness of the drawing process, as well as the actual value of the ticket sales. The drawn numbers may be biased to favor specific players, and / or the lottery operator may advertise a jackpot that is significantly lower (but still attractive enough) than the ticket sales. It is certainly suspicious that many lotteries constantly advertise perfectly round-numbered jackpots like $1M.

Case in point, Hot Lotto⤴ has suffered one of the most famous lottery fraud scandals (not necessarily the worst). Other known frauds include a Serbian lottery announcing the numbers before they were drawn⤴ and Chinese lottery operators reportedly stealing jackpot money⤴. Other frauds that may have occurred might never be uncovered.

We want to overcome all the above problems by implementing a new lottery game based on a decentralized, trustless, censorship-resistant, and cryptographically verified platform: the EVM.

Game Description

For scalability reasons the game will run on the Polygon PoS blockchain⤴, which is compatible with Ethereum and can run Solidity programs with little to no modifications.

Players join the game by buying one or more tickets. When buying a ticket a player chooses 6 or more different numbers between 1 and 90 inclusive.

6 different random numbers between 1 and 90 inclusive are securely drawn by the system once a week, and all tickets matching two or more of the drawn numbers are awarded a prize. We use the ChainLink VRF⤴ to draw the 6 random numbers securely.

Tickets with more than 6 numbers, which we call higher-order tickets throughout this paper, are in every possible regard treated as if the player purchased all possible 6-combinations that can be chosen from those numbers. For example, a ticket with 8 numbers is equivalent to different 6-number tickets, and in general a ticket with numbers (with ) is equivalent to different 6-number tickets, with being the binomial coefficient⤴ "k choose 6" representing the number of ways to choose 6 elements from a set of .

The entire project uses the Dai stablecoin as a currency (see MakerDAO⤴ for more information): tickets are paid for in Dai and all prizes and revenues are in Dai. This way the project is not subject to wild price fluctuations that other cryptocurrencies may be subject to.

Given that the target price of a 6-number ticket is $1.50, the price of a higher-order ticket with numbers is calculated multiplying $1.50 by the binomial coefficient . This results in the following prices:

| Numbers in the ticket | Number of 6-combinations | Price |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1 | $ 1.50 |

| 7 | 7 | $ 10.50 |

| 8 | 28 | $ 42.00 |

| 9 | 84 | $ 126.00 |

| 10 | 210 | $ 315.00 |

| 11 | 462 | $ 693.00 |

| 12 | 924 | $ 1,386.00 |

| 13 | 1716 | $ 2,574.00 |

| 14 | 3003 | $ 4,504.50 |

| 15 | 5005 | $ 7,507.50 |

| 16 | 8008 | $ 12,012.00 |

| 17 | 12376 | $ 18,564.00 |

| 18 | 18564 | $ 27,846.00 |

| 19 | 27132 | $ 40,698.00 |

| 20 | 38760 | $ 58,140.00 |

Five different winning categories are defined:

- tickets matching exactly 2 of the drawn numbers,

- tickets matching exactly 3 of the drawn numbers,

- tickets matching exactly 4 of the drawn numbers,

- tickets matching exactly 5 of the drawn numbers,

- and tickets matching all 6 drawn numbers.

ExaLotto keeps a separate prize for each category. The five prizes are funded by the revenue generated by the ticket sales as explained in Prize Allocation.

At the end of a round, each winning category may have zero or more winners. If there are zero, as we expect to often be the case for the 6-match category, the prize of that category is carried over to the next round; otherwise it is made available for withdrawal by the players owning the winning tickets, and the corresponding prize of the same category in the next round starts over from zero. An exception to this rule is the prize of the 6-match category (aka the jackpot), which is treated specially as described in Prize Allocation.

An important property of the game is that 6-number tickets only win a prize from their highest winning category. For example, a ticket matching 4 numbers will also match 3 numbers in several ways and 2 numbers in several ways, but the player will only be allowed to withdraw a prize from the 4-match category. This is not true for higher-order tickets, for reasons explained in Prize Allocation, and despite the fact that every higher-order ticket is treated exactly as the set of all possible 6-combinations in it.

The whole game and its DAO are managed on-chain at all times. The ChainLink VRF invocation is the only part that runs outside of the EVM, but the ChainLink network is still a decentralized system. We do not use any centralized components.

DAO Management

As mentioned above, ExaLotto is a decentralized lottery game managed by a DAO. Voting power is

proportional to an ERC20⤴ token with trading symbol EXL.

The DAO is implemented using standard opensource smartcontracts provided by

OpenZeppelin⤴. Namely we use a Governor⤴ and a

TimelockController⤴ with some added functionality. The EXL

token is an ERC20Votes⤴ token with some added functionality. See the

Governance section for an in-depth description about the implementation.

The EXL token is burnable but not mintable. The initial total supply is 1,000,000,000 EXL with

18 decimals, or equivalently 1e27 EXL-wei.

The EXL token provides its holder with two benefits:

- they can participate in the DAO by making proposals and casting votes,

- they receive a proportional share of the revenue.

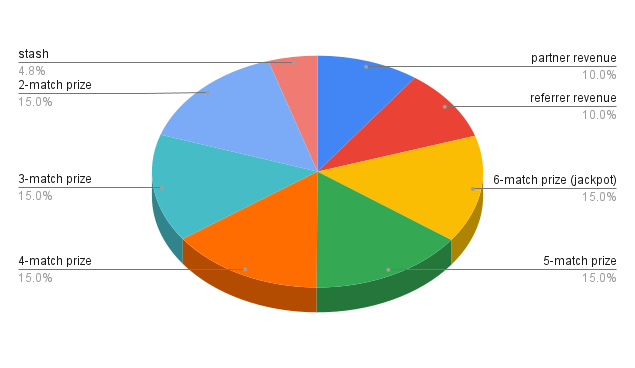

The revenue generated by the ticket sales is divided as follows:

- 10% is known as the partner revenue and is distributed among

EXLholders proportionally to theirEXLshare, - 10% is known as the referral revenue and is distributed among referrers or

EXLholders as described in Referral Program, - and the remaining 80% is used to fund the prizes.

The revenue is checkpointed weekly upon round closure, and the distribution is based on a withdrawal model. The withdrawal model is common practice in the Ethereum ecosystem due to security and scalability reasons: distributing tokens by transferring them manually to N recipients would require linear algorithms that may not scale. Instead, our smartcontracts provide cheap methods to perform withdrawals and the website provides the necessary UI to trigger them.

Referral Program

ExaLotto allows third parties known as referrers to sell tickets on ExaLotto's behalf. The incentive is that the referrer earns 10% of the revenue it generates. This referral program is entirely managed by the lottery smartcontract.

Referrers register themselves on the ExaLotto website, which generates a referrer-specific code and provides an HTML snippet they can embed in their own website; the snippet creates an ExaLotto widget in the page where a visitor can buy ExaLotto tickets. The widget uses the referral code to interact with ExaLotto's smartcontacts, which in turn attribute the referral revenue for the ticket to the corresponding referrer. At the end of a round the referrer can withdraw the generated revenue.

When no referral code is used and a ticket is sold on the main ExaLotto website, the 10% share

allocated for the referrer is actually distributed among the delegating EXL holders as described

in DAO Management. In other words, when no referral code is used EXL holders

receive a total 20% of the ticket value.

Prize Allocation

As described in the previous sections, 20% of the revenue from the ticket sales is distributed among partners and referrers; the remaining 80% is used to fund the game. This 80% is divided in 6 parts: 18.8% is used to fund the prizes of each winning category and the remaining 6% is stashed to fund the jackpot of the next round in case one or more players match all 6 drawn numbers; that way the jackpot is never zero.

The total revenue generated by the ticket sales is divided as follows:

At the end of a round each category may have zero or more winners. If there are zero winners the prize money for that category is carried over to the next round, while if there are one or more the category prize is divided equally among them.

Through the rest of this paper we will call -number tickets "-tickets" for brevity.

ExaLotto has two important properties:

- 6-tickets must be rewarded only from their highest winning category (e.g. a ticket with 4 matches will not also be rewarded for matching 3 or 2 numbers in several ways);

- tickets with more than 6 numbers must be treated exactly as if the player purchased all possible 6-tickets with those numbers, which are for an -ticket.

If a player buys the following 6-ticket:

and the following numbers are drawn:

property #1 dictates that the player will receive a prize from the 4-match category but not prizes from the 3-match category or from the 2-match one.

Higher-order tickets however make things more complicated. Let’s suppose a player bought the following 8-ticket:

and the same numbers as in the example above were drawn, so there were 4 matches. An 8-ticket corresponds to many 6-tickets, some of which contain the 4 matching numbers; so the prize from the 4-match category must be weighted accordingly. The 6-tickets containing the 4 matching numbers are:

They are 6 in total and can be counted as the number of ways to choose the remaining 2 numbers that can be added to the 4 matching numbers to form a 6-ticket. In formulas:

where is the cardinality of the ticket (8 in this case) and is its highest winning category.

Next we observe that not all 6-combinations represented by the 8-ticket have all four matching numbers. The following table provides the exhaustive list of combinations, showing that some of them match only 3 or 2 of the drawn numbers (highlighted in bold):

| # | 6-combination | # of matches | # of tickets in that rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 4 | |

| 2 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 | 4 | |

| 3 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 | 4 | |

| 4 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 | 4 | |

| 5 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 | 4 | |

| 6 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8 | 4 | |

| 7 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 | 3 | |

| 8 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 | 3 | |

| 9 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 10 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 11 | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 | 3 | |

| 12 | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 | 3 | |

| 13 | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 14 | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 15 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 | 3 | |

| 16 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 | 3 | |

| 17 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 18 | 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 19 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 | 3 | |

| 20 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 | 3 | |

| 21 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 22 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 | 3 | |

| 23 | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 | |

| 24 | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 | |

| 25 | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 | |

| 26 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 | |

| 27 | 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 | |

| 28 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | 2 |

There are 6-combinations in total, of which:

- 6 match 4 numbers,

- 16 match 3 numbers,

- and 6 match 2 numbers.

The rightmost column of the table shows the formula to calculate the number of 6-combinations in each winning category, which can be generalized as:

with:

- = cardinality of the ticket,

- = highest winning category,

- = winning category.

So the generic -ticket matching of the drawn numbers must be awarded prizes from the -match category.

Note that the binomial coefficient is defined to be zero for every , and thanks to that our formula works for 6-tickets just as well. For example, for a 6-ticket matching 4 numbers (that is, and ) we have

so that the second coefficient becomes 0 for every .

As explained earlier, we allocate the same fraction of the revenue for all 5 winning categories, . We found this to be the fairest possible allocation. In fact, in order to award the fairest possible prizes, the share of a given category must be inversely proportional to the probability of winning and directly proportional to the expected⤴ number of winners. In other words:

- it is fair to allocate a larger share to the winners of a higher category because they have a lower probability of winning; and

- it is fair to allocate a larger share to the winners of a lower category because we expect a higher number of winners.

So we have two conflicting criteria that balance each other out, as we show formally in the following.

For a given category we can call the probability of winning in that category and the expected number of winners . We can use to indicate the total number of 6-combinations played in a round. is a binomial variable⤴ with expected value . Based on the two proportionality criteria above, the share of the revenue allocated to the prize for category can be measured as:

This measure does not depend on or any other -dependent parameter, so all shares must have the same size. This is unlike most other lotteries, which allocate seemingly arbitrary or inadequately explained shares of the revenue to the various categories.

Scaling Challenges

A lottery game is based on the core idea that a large number of players pays a small amount each, so we need our implementation to scale to large amounts of tickets, e.g. 1 million per round or even more.

Once again let's consider the number of expected winners for a category . is the probability of matching exactly numbers. Since is highest for low values of (matching 2 numbers is easier than matching 6), our worst case (highest number of tickets in a winning category) is .

The probability of an event is calculated by dividing the number of favorable cases by the number of total cases. Assuming all tickets have 6 numbers for simplicity, the number of total cases is . Let's then calculate the number of favorable cases for matching exactly 2 numbers, which is our worst case because the 2-match category will often give us the largest amount of processing work.

The number of ways to match exactly 2 numbers is the number of ways to choose 2 of the drawn numbers times the number of ways to choose 4 other numbers among the ones that were not drawn:

So our probability is:

Now, with

yields approximately 46,485 winners. It is very hard to run any kind of algorithm on 46,485 elements on the EVM, and it is impossible if storage is involved in any way, as the gas cost would vastly exceed the limit of 30,000,000 gas units. Not only this means we will not be able to implement a naive drawing algorithm that scans all tickets and finds the winners by counting the matches of each one; even if somehow we knew the list of winners for a category we would not be able to attribute or transfer their prizes.

Ticket Indexing

The problem discussed above poses two fundamental requirements on our implementation:

- Prize attribution must be based on a withdrawal model: the lottery smartcontract will not be able to send any money to the winning players, or even just keep track of their prize balance. Rather, the players will have to perform a transaction that withdraws the prize of a ticket (if any). This is in line with the best practices in terms of security and scalability within the Ethereum ecosystem.

- We will not be able to identify the winning tickets of a category in any way, but we still need to know the number of winning 6-combinations in that category in order to calculate the prize that can be withdrawn by each winner. For example, if tickets win in the 2-match category (assuming all 6-tickets for simplicity), they must be able to withdraw 1/k-th of the prize allocated for the category, so we need to know .

The number of winning 6-combinations described in point #2 must somehow be readily available in storage. If we cannot calculate it at drawing time by scanning all tickets then it must be calculated progressively as tickets are sold. Since the 6 drawn numbers are not known while the tickets are sold, we need to progressively calculate and update the number of winners in all 622,614,630 possible cases. As it turns out, this is actually feasible and does not inflate gas costs to unacceptable levels. In the following sections we will describe the required algorithms and analyze the resulting gas costs.

Indexing Algorithm

Let's define a bijection from the first 90 positive naturals 1, 2, 3, ... to the first 90 primes 2, 3, 5, ...

We have:

The first 90 positive naturals correspond to the numbers that can be played and drawn in ExaLotto.

Let's call the above table so that is the -th prime.

A ticket with 6 numbers , , , , , , independently of their order, can be identified by the following product:

Storing is not a problem thanks to the 256-bit integers used by Solidity. For a 20-number ticket, which has a hefty base price of $58,140 as per the price table above, we have:

So the product for such a ticket will take less than 177 bits.

We can now index all tickets in a Solidity mapping whose keys are such products and whose values

are the number of 6-combinations containing those numbers. Then, at draw time, the number of

6-combinations with 6 matches is readily available in storage at the slot of the mapping

corresponding to:

with , , , , , and being the 6 drawn numbers.

With a small abuse of terminology we will call the numbers ticket hashes. They are not

really hash numbers in the traditional cryptographic sense because a hash is supposed be easy to

calculate and hard to invert, while our ticket hashes are fairly easy to invert. We still think the

word "hash" is appropriate because we use these numbers as indices in associative data structures

(namely Solidity mappings) and they are also deterministic and unique for a given set of numbers

independently of their order.

Our hash system provides an easy way to find in O(1), but of course we need to repeat the process for all other winning categories. It will get more expensive for other categories because there will be many ways to choose 2 numbers out of the 6 drawn ones, many ways to choose 3, etc.

In the following we will rank our ticket hashes based on the cardinality of a subset of numbers. For example, the 6-ticket

has:

- 15 2-hashes (, , etc.),

- 20 3-hashes (, , etc.),

- 15 4-hashes (, , etc.),

and so on.

We will use the same mapping to index hashes of all ranks, and that is not a problem because

hashes of different ranks cannot collide thanks to the fact that they are products of prime numbers.

If two hashes collide it means they represent the same unordered set of numbers.

In total, the drawing algorithm will need to look up:

mapping slots, which does not pose any scalability challenge.

That is also the number of mapping slots the ticket purchase algorithm will have to write for a

6-number ticket, which is somewhat more critical. Writing a non-zero value to a storage slot that is

initially zero costs 20,000 gas units, as implied by the official specification⤴

(we are assuming cold access). Indexing a 6-number ticket whose numbers have never been played

before in the current round therefore costs gas units. With a pessimistic

gas cost of 500 Gwei, that makes for a 0.57 POL gas fee (POL is the native currency of the

Polygon PoS blockchain). Assuming 1 POL = 1 USD for simplicity, the 0.57 POL fee adds to a $1.50

ticket value for a total of $2.07 for a 6-number ticket, which we deem acceptable.

For higher-order tickets the gas fee obviously gets much worse in absolute terms, but it actually gets better in relative terms. For example, an 8-ticket will need to write the following amount of storage slots:

Assuming cold access for all of them for the worst case we get a gas cost of units, or 2.38 POL at a 500 Gwei gas cost. The ticket itself would cost $42.00, so the gas fee is only ~5.67% of the ticket price as opposed to 38% for the 6-ticket. That is because the ticket price is proportional to the number of 6-combinations ( for an -ticket), while the gas fee is proportional to the number of storage slots ( for an -ticket). When grows, the latter grows slower than the former.

Here is a breakdown of all relative gas costs for the tickets up to 20 numbers:

| ticket rank | # of written slots | gas fee (POL) | ticket price | gas fee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 57 | 0.57 | $1.50 | 38.00% |

| 7 | 119 | 1.19 | $10.50 | 11.33% |

| 8 | 238 | 2.38 | $42.00 | 5.67% |

| 9 | 456 | 4.56 | $126.00 | 3.62% |

| 10 | 837 | 8.37 | $315.00 | 2.66% |

| 11 | 1474 | 14.74 | $693.00 | 2.13% |

| 12 | 2497 | 24.97 | $1,386.00 | 1.80% |

| 13 | 4082 | 40.82 | $2,574.00 | 1.59% |

| 14 | 6461 | 64.61 | $4,504.50 | 1.43% |

| 15 | 9933 | 99.33 | $7,507.50 | 1.32% |

| 16 | 14876 | 148.76 | $12,012.00 | 1.24% |

| 17 | 21760 | 217.60 | $18,564.00 | 1.17% |

| 18 | 31161 | 311.61 | $27,846.00 | 1.12% |

| 19 | 43776 | 437.76 | $40,698.00 | 1.08% |

| 20 | 60439 | 604.39 | $58,140.00 | 1.04% |

Gas fees are usually much lower than 500 Gwei and not all tickets will perform cold access on all slots, so the average ticket prices will be much better.

The goal of the rest of this section is to write a Solidity function called indexTicket that takes

6 or more numbers between 1 and 90 inclusive (the numbers chosen by the player when purchasing the

ticket) and indexes all of their possible 2-combinations, 3-combinations, 4-combinations,

5-combinations, and 6-combinations in a data structure for later retrieval by the

drawing algorithm.

The indexing data structure, which we will call just index, is a Solidity mapping from ticket

hashes of all ranks to the number of 6-combinations matching each rank-hash. Ticket indices are

round-specific, meaning that an index instance will only count the 6-combinations of a single

round.

The signature of our indexTicket function will be:

function indexTicket(

mapping(uint256 => uint) storage index,

uint8[] calldata numbers // must have at least 6 elements

) public {

// ...

}

Indexing 6-tickets is easy: since they have only one 6-combination we just need to increment the

number of 6-combinations associated to each rank-hash of the ticket by 1. A version of indexTicket

that is for 6-tickets only could be written as follows:

function indexTicket6(

mapping(uint256 => uint) storage index,

uint8[6] calldata numbers

) public {

uint256 p0 = getPrime(numbers[0]);

uint256 p1 = getPrime(numbers[1]);

uint256 p2 = getPrime(numbers[2]);

uint256 p3 = getPrime(numbers[3]);

uint256 p4 = getPrime(numbers[4]);

uint256 p5 = getPrime(numbers[5]);

index[p0 * p1]++;

index[p0 * p2]++;

index[p0 * p3]++;

index[p0 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p2]++;

index[p1 * p3]++;

index[p1 * p4]++;

index[p1 * p5]++;

index[p2 * p3]++;

index[p2 * p4]++;

index[p2 * p5]++;

index[p3 * p4]++;

index[p3 * p5]++;

index[p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p3]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p3]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p3]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p4]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p1 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p2 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p2 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p2 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p3]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p2 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p3 * p4]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p3 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p2 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p1 * p2 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

index[p0 * p1 * p2 * p3 * p4 * p5]++;

}

where getPrime(i) returns the -th prime as per the bijection above. The implementation of

getPrime itself is fairly straightforward because we will only ever deal with the first 90 primes,

so we will not discuss it here.

Higher-order tickets make things more complicated because each rank-hash may be covered by more than one 6-combination. For example, a 7-ticket has exactly 5 6-combinations for every 2-hash because given the 2 numbers corresponding to the 2-hash they can be counted as the number of ways to choose the remaining 4 numbers (). Because of that, in order to write the full indexing algorithm we will need a Solidity implementation of the binomial coefficient⤴. We can create an efficient one using the well known properties:

In code:

function choose(uint n, uint k) private pure returns (uint) {

if (k > n) {

return 0; // base case 1

} else if (k == 0) {

return 1; // base case 2

} else if (k * 2 > n) {

return choose(n, n - k); // optimize by property (1)

} else {

return (n * choose(n - 1, k - 1)) / k; // recurse by property (2)

}

}

We can now move on to the full implementation.

At its core the indexing algorithm needs to scan all possible 2-combinations, 3-combinations, etc.

in the ticket. Let's start out with a nested for loop structure to scan all combinations:

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < p.length; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < p.length; i1++) {

// 2-combination given by (i0, i1)

for (uint i2 = i1 + 1; i2 < p.length; i2++) {

// 3-combination given by (i0, i1, i2)

for (uint i3 = i2 + 1; i3 < p.length; i3++) {

// 4-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3)

for (uint i4 = i3 + 1; i4 < p.length; i4++) {

// 5-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3, i4)

for (uint i5 = i4 + 1; i5 < p.length; i5++) {

// 6-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3, i4, i5)

}

}

}

}

}

}

The p variable referred to by the p.length expressions is our array of numbers converted to the

corresponding primes, which we can initialize as follows:

uint256[] memory p = new uint256[](numbers.length);

for (uint i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

p[i] = getPrime(numbers[i]);

}

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < p.length; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < p.length; i1++) {

// ...

Each slot of the index, corresponding to a -hash of rank , needs to be incremented by the

number of 6-combinations containing the numbers of the hash. The increment is therefore the

number of ways to choose the other numbers, or where is

numbers.length (same as p.length). Since is fixed we can calculate this binomial coefficient

at the beginning for all s:

uint combinations2 = choose(numbers.length - 2, 4);

uint combinations3 = choose(numbers.length - 3, 3);

uint combinations4 = choose(numbers.length - 4, 2);

uint combinations5 = numbers.length - 5; // choose(numbers.length - 5, 1)

We do not need combinations6 because the number of 6-combinations corresponding to a given 6-hash

is obviously 1.

The updated algorithm is:

function indexTicket(

mapping(uint256 => uint) storage index,

uint8[] calldata numbers

) public {

uint combinations2 = choose(numbers.length - 2, 4);

uint combinations3 = choose(numbers.length - 3, 3);

uint combinations4 = choose(numbers.length - 4, 2);

uint combinations5 = numbers.length - 5;

uint256[] memory p = new uint256[](numbers.length);

for (uint i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

p[i] = getPrime(numbers[i]);

}

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < p.length; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < p.length; i1++) {

index[p[i0] * p[i1]] += combinations2;

for (uint i2 = i1 + 1; i2 < p.length; i2++) {

index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2]] += combinations3;

for (uint i3 = i2 + 1; i3 < p.length; i3++) {

index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3]] += combinations4;

for (uint i4 = i3 + 1; i4 < p.length; i4++) {

index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4]] += combinations5;

for (uint i5 = i4 + 1; i5 < p.length; i5++) {

index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4] * p[i5]]++;

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Drawing and Withdrawing Algorithms

Based on what we have discussed so far, the drawing algorithm is made up of three phases:

- request random words from the ChainLink VRF⤴ and consequently determine the 6 drawn numbers;

- find the number of winning 6-combinations in each category;

- checkpoint the revenue and make it available to partners and referrers for withdrawal.

Determining the 6 Random Numbers

The ChainLink VRF can produce one or more 256-bit random words in exchange for a payment in LINK

tokens. The lottery smartcontract requests 6 words to ChainLink and then uses them to determine 6

random numbers between 1 and 90 inclusive without repetitions.

We hereby discuss the implementation of a Solidity function that takes the random 256-bit words returned by the VRF and returns the 6 random numbers:

function getRandomNumbersWithoutRepetitions(

uint256[] calldata randomWords

) pure returns (uint8[6] memory numbers) {

// ...

}

Since the drawn numbers must not have repetitions we can choose them by taking an array of the first 90 integers, production a random permutation based on the input words, and returning the first 6. We can use the Fisher-Yates shuffle⤴ for that purpose.

Here is a basic implementation in Solidity:

uint8[90] memory source;

for (uint8 i = 1; i <= 90; i++) {

source[i - 1] = i;

}

for (uint i = 0; i < source.length; i++) {

uint j = i + (randomWords[i] % (90 - i));

uint8 temp = source[i];

source[i] = source[j];

source[j] = temp;

}

for (uint i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

numbers[i] = source[i];

}

Note that numbers is the 6-element array returned by our getRandomNumbersWithoutRepetitions

function.

The algorithm written so far requires 90 elements in randomWords. We cannot use the same word

through the whole algorithm because a 256-bit word does not have enough information to scramble 90

elements. A single word can give us at most

random indices.

However we can reduce our usage to just 6 words. The Fisher-Yates algorithm changes the elements of the array in order and never changes an element more than once, so we do not need to go through the whole array, we can simply stop at index 5:

function getRandomNumbersWithoutRepetitions(

uint256[] calldata randomWords // assume 6 elements

) pure returns (uint8[6] memory numbers) {

uint8[90] memory source;

for (uint8 i = 1; i <= 90; i++) {

source[i - 1] = i;

}

for (uint i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

uint j = i + (randomWords[i] % (90 - i));

uint8 temp = source[i];

source[i] = source[j];

source[j] = temp;

}

for (uint i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

numbers[i] = source[i];

}

}

We can further simplify the algorithm by writing our numbers directly to numbers rather than

modifying source and copying the first 6 elements:

function getRandomNumbersWithoutRepetitions(

uint256[] calldata randomWords // assume 6 elements

) pure returns (uint8[6] memory numbers) {

uint8[90] memory source;

for (uint8 i = 1; i <= 90; i++) {

source[i - 1] = i;

}

for (uint i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

uint j = i + (randomWords[i] % (90 - i));

numbers[i] = source[j];

source[j] = source[i];

}

}

Note: in theory a single 256-bit word has enough information to infer all 6 indices we use in this last version. In fact we have:

Or, equivalently:

But in practice it is very hard to do so while not affecting bias. Some bias will always be present since 90 does not divide , but it is virtually non-existent because is many orders of magnitude larger than , or 16 (see Modular exponentiation⤴ for information on how to calculate it). The bias we have means the first 16 elements of our [1, 90] range have one out of extra chances of being extracted compared to the other 74. If we extracted all 6 indices from the same 256-bit word we would be consuming ~33 bits for the first 5 indices and be left with 223 for the last. We have , so the first 38 elements of the [1, 90] range would now have one out of extra chances of being extracted. It is still virtually non-existent, but we would rather not have this inconsistency.

Finding the Winners

The goal of this phase of the drawing algorithm is to yield five unsigned integer numbers corresponding to the number of winning 6-combinations in each category.

Note that we need to count 6-combinations rather than tickets because, as explained previously, all higher-order tickets are treated exactly as if the player purchased a set of 6-tickets corresponding to all 6-combinations in the higher-order ticket. The price of a ticket is proportional to the number of 6-combinations in it, so a fair prize must also be proportional.

Once we have these five numbers we can store them in a data structure associated to the current round of the lottery, and all prize withdrawals will refer to that structure to determine the prize amount.

We will now discuss the implementation of a Solidity function called findWinners that calculates

these numbers. The function needs two pieces of input: the index data structure described in the

Indexing Algorithm section and the 6 drawn numbers. It will return 5 unsigned

integers representing the number of winning 6-combinations in each category.

function findWinners(

mapping(uint256 => uint) storage index,

uint8[6] memory numbers

) public view returns (uint[5] memory winners) {

winners = [

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 2 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 3 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 4 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 5 matches

uint(0) // # of 6-combinations with 6 matches

];

// ...

}

First off, in order to work on the index we need to initialize the 6 prime numbers corresponding

to the drawn numbers as usual:

uint256[6] memory p = [

uint256(getPrime(numbers[0])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[1])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[2])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[3])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[4])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[5]))

];

Similarly to the ticket indexing algorithm, findWinners will also use a

nested for loop structure to scan all possible 2-, 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-combinations of the drawn

numbers, the only difference being that this time there are exactly 6 numbers and we will therefore

find exactly 57 combinations, of which only one 6-combination.

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < 6; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < 6; i1++) {

// 2-combination given by (i0, i1)

for (uint i2 = i1 + 1; i2 < 6; i2++) {

// 3-combination given by (i0, i1, i2)

for (uint i3 = i2 + 1; i3 < 6; i3++) {

// 4-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3)

for (uint i4 = i3 + 1; i4 < 6; i4++) {

// 5-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3, i4)

for (uint i5 = i4 + 1; i5 < 6; i5++) {

// 6-combination given by (i0, i1, i2, i3, i4, i5)

}

}

}

}

}

}

We can now access the index and copy the relevant values to the winners array accordingly:

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < 6; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < 6; i1++) {

winners[0] += index[p[i0] * p[i1]];

for (uint i2 = i1 + 1; i2 < 6; i2++) {

winners[1] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2]];

for (uint i3 = i2 + 1; i3 < 6; i3++) {

winners[2] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3]];

for (uint i4 = i3 + 1; i4 < 6; i4++) {

winners[3] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4]];

for (uint i5 = i4 + 1; i5 < 6; i5++) {

winners[4] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4] * p[i5]];

}

}

}

}

}

}

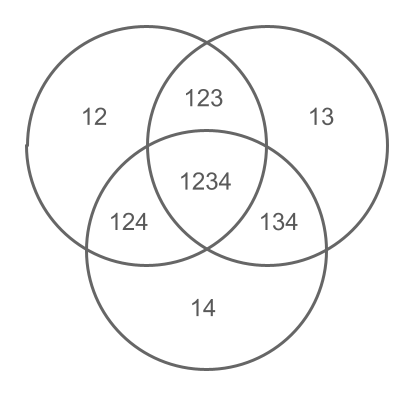

The algorithm written so far has a double-counting problem. The counts associated to the ticket hashes of each rank are simply being added up, but the sets they represent are not disjoint. Representing all the involved sets is too complicated but the following branch of the Venn diagram is sufficient to understand the problem:

The diagram assumes that the drawn numbers are 1, 2, 3, 4, and two more. The area labeled with 12

is the set of all 6-combinations containing 1 and 2, the area labeled with 123 is the set of all

6-combinations containing 1, 2, and 3, and so on.

Since the sets are not disjoint, the cardinalities of the areas labeled 123, 124, 134, and

1234 have been counted several times. This would violate property #1 of ExaLotto (6-combinations

winning in category must not also be awarded a prize for matching numbers in several

ways, numbers in several ways, etc.) because the winners from a category are also being

counted in all categories beneath.

The above Venn diagram shows us that we need to remove the number of winners of category from

all categories (for all such that ) as many times as there are ways to choose

elements out of , or , because that is how we can count all possible

-intersections that are being extra-counted in the category. For example, the area 123 is

being counted in the 2-match category once for every contributing 2-match set, that is: 12, 13,

and 23. Those sets can be found by choosing 2 elements out of 3.

The coefficients can be pre-calculated since they only depend on category numbers. The last piece of our algorithm therefore is:

winners[3] -= winners[4] * 6;

winners[2] -= winners[3] * 5 + winners[4] * 15;

winners[1] -= winners[2] * 4 + winners[3] * 10 + winners[4] * 20;

winners[0] -= winners[1] * 3 + winners[2] * 6 + winners[3] * 10 + winners[4] * 15;

Here is the full algorithm for clarity:

function findWinners(

mapping(uint256 => uint) storage index,

uint8[6] memory numbers

) public view returns (uint[5] memory winners) {

winners = [

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 2 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 3 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 4 matches

uint(0), // # of 6-combinations with exactly 5 matches

uint(0) // # of 6-combinations with 6 matches

];

uint256[6] memory p = [

uint256(getPrime(numbers[0])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[1])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[2])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[3])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[4])),

uint256(getPrime(numbers[5]))

];

for (uint i0 = 0; i0 < 6; i0++) {

for (uint i1 = i0 + 1; i1 < 6; i1++) {

winners[0] += index[p[i0] * p[i1]];

for (uint i2 = i1 + 1; i2 < 6; i2++) {

winners[1] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2]];

for (uint i3 = i2 + 1; i3 < 6; i3++) {

winners[2] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3]];

for (uint i4 = i3 + 1; i4 < 6; i4++) {

winners[3] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4]];

for (uint i5 = i4 + 1; i5 < 6; i5++) {

winners[4] += index[p[i0] * p[i1] * p[i2] * p[i3] * p[i4] * p[i5]];

}

}

}

}

}

}

delete p;

winners[3] -= winners[4] * 6;

winners[2] -= winners[3] * 5 + winners[4] * 15;

winners[1] -= winners[2] * 4 + winners[3] * 10 + winners[4] * 20;

winners[0] -= winners[1] * 3 + winners[2] * 6 + winners[3] * 10 + winners[4] * 15;

}

Revenue Checkpointing

// TODO